Every year would have a bloody beginning at a small village, Lalgarh, situated in the interiors of Jhargram district, West Bengal.

As a small boy, Bapi Mahata recalls how elders of his village, along with several others from neighbouring areas, would gather to make a journey into the dense jungles, only to return brandishing blood-speared arrows, axes, swords and knives, along with a load of freshly-slaughtered animal carcasses – their prized kill.

An annual affair, this was a part of their celebrations; a grand feast of wild animals, some of which continue to be endangered.

“The hunting season mostly coincides with a full moon and is more a part of the celebration. Thousands of wild animals, many of which are already dwindling in numbers, would be mercilessly slaughtered for fun, as part of the feast. Growing up, it always disgusted me, especially to see the indiscriminate killing of protected wildlife in the name of ritualistic hunting,” says Bapi, who is one of the few alternate voices in the village fighting for the past three years to put an end to this.

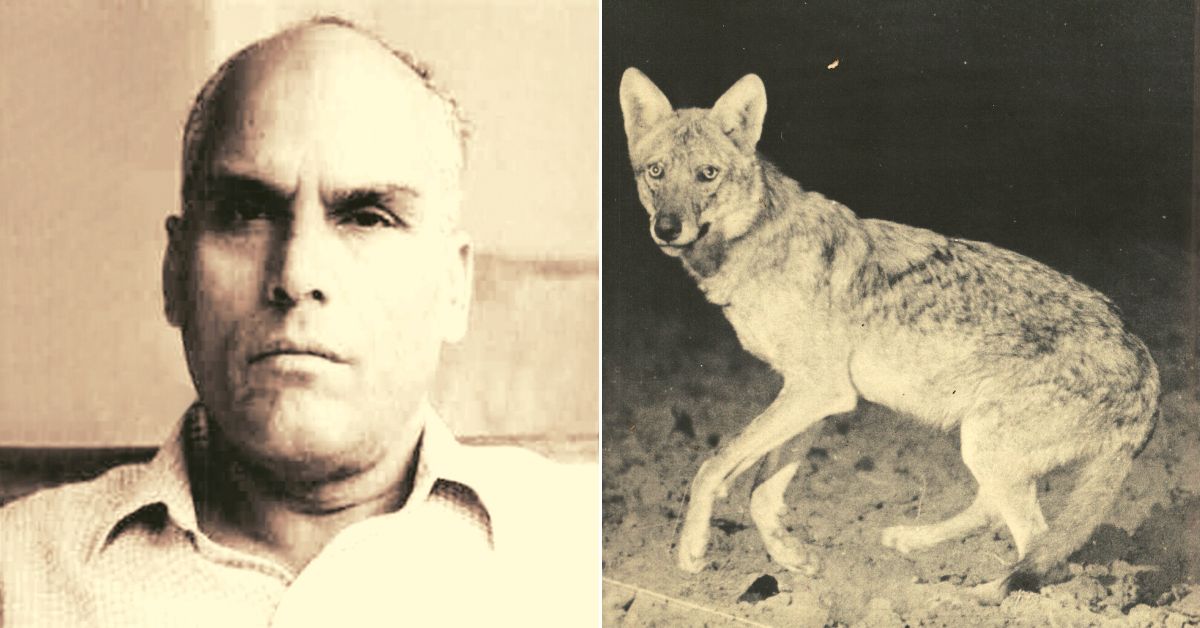

In 2017, his growing urge to stop ritualistic hunting and poaching pushed him to join a wildlife protection NGO, Human & Environment Alliance League (HEAL), as an active volunteer. He is one of the 60 volunteers at HEAL who have been tirelessly trying to track down hunters and stop this practice across the forests of West Bengal.

With their aid, HEAL has been able to rescue over 250 animals, about 160 birds and made at least 15 arrests in the past few years.

Talking about the scale of impact achieved by HEAL in the past three years since its inception in 2017, one of its founding members, Meghna Banerjee says, “In this line of work, there is a lot of resistance, myths and a sense of secrecy guarding the act of hunting. We have had to penetrate all of that to be able to not only ensure the implementation of wildlife protection laws but also change the perception of people on a grassroots level.”

One of the major challenges has been the lack of awareness about this practice and the myths surrounding the laws that protect wildlife.

“While many would know about the hunting and poaching of megafauna for illegal wildlife trade, in various parts of the country, especially in states like Rajasthan or even the North-East, not many are aware of the situation in the interior parts of Bengal. The nature of hunting here is different from poaching for livelihood or illegal trade. It is associated with and ingrained in the culture; it is part of their rituals, which makes it more difficult to stop,” she says.

Tracking Ritualistic or Recreational Hunting

Although officially started in 2017, HEAL members, along with their volunteers, began to investigate and document ritualistic killings for the hunting festival since 2016.

According to their findings, most hunts start around January or February and last till June. Around this time, large groups of hunters from various parts of the state including many from ST communities, travel long distances often by train, to reach the hunting destinations. A report by Conservation India states that the hunting festival attracts more than 50,000 people every year, and that the hunters on each occasion may range between 1000 to 15,000 at a time.

“Scores of people assemble at the hunting locations, sometimes along with their dogs, and then participate in the slaughter of thousands of birds, reptiles, mammals etc, all of which are supposedly protected under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. From fishing cats, jackals, Bengal monitor lizards, jungle cats, porcupines, hyenas, Bengal foxes, wild boars, pangolins, civets to birds such as owls, barbets, jacanas, coucals and many more are killed during this time. In 2018, even a tiger was killed in Jhargram’s Lalgarh. While for some it is a part of the ritual, many recreational hunters join in for fun and make it more of a competition of killing as many as possible. Considering the large number of people participating in this, we can only imagine the scale of the massacre,” Meghna explains.

She points out that it was the shocking number of hunters that spurred HEAL into action, pushing them to seek assistance from law enforcement bodies. Over the years, their efforts of tracking down hunters, intercepting such assemblies, and rescuing wildlife have been possible with the association of the Forest Department and the Railway authorities, especially in parts of East Medinipur and Howrah, in South Bengal.

Misconceptions and Myths about Hunting Rights

Meghna adds that before the embargo on ritualistic hunting by the Calcutta High Court, most hunters would carry out their acts without any fear of the law.

Many even assumed that a certain exemption would apply to indigenous tribes hunting these wild animals. “There are a lot of misconceptions and myths around the law, both among the people as well as some authorities that bolster their resolve to continue this practice without any fear. But under the Wildlife Protection Act, no such exemption is provided even for forest dwellers, who traditionally were dependent on hunting for their livelihood. Hunting of wildlife animals is illegal under WPA 1972 making it a cognizable and non-bailable offence, punishable with imprisonment, which may extend up to seven years, and/or a fine, which may extend up to Rs. 25,000. Through HEAL we are trying to clarify this and implement strict on-ground measures that deter hunting,” adds Meghna, who is also a lawyer.

Even under the Scheduled Tribes and other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 (FRA) traditional hunting of wild animals is stated as illegal. As per this law, the rights of forest dwellers excludes hunting or trapping and extracting a part of the body of any species of a wild animal.

Legal course to Combat Hunting Practices

While these laws have been in place for several years, the weak on-ground implementation was one of the reasons for the unabashed hunting practices.

Hence in 2018, HEAL decided to intervene judicially, by filing a public interest litigation (PIL) before the Calcutta High Court to put an end to the mass hunting in East Medinipur and Howrah districts of West Bengal, especially during the Faloharini Kali Pujo hunt fest. This hunt fest would take place every year between May and June and would continue for approximately a week, creating an irreversible impact on the local wildlife. Over 5,000 animals would die annually just in this one festival.

Owing to HEAL’s incessant efforts, the Calcutta High Court, eventually, on May 10, 2018, passed an interim order that directed the West Bengal Forest Department to control hunting during Faloharini. From the district magistrate, superintendents of police to railway authorities in East Medinipur and Howrah districts, all were directed to work in tandem with the Forest Department to stop and prevent the hunt. This interim order finally was confirmed on April 18, 2019.

The judicial step then translated into grassroots-level implementation with increased patrolling in affected regions, that deterred people from carrying weapons or poached animals. Various awareness initiatives such as anti-hunting audio messages in railway stations, posters, police deployment to dissuade hunters and making common hunting spots inaccessible to them, slowly began to create an impact.

Alongside the authorities, HEAL’s 80-member team and volunteer group, Zero Hunting Alliance, continued to monitor the movement of hunting groups and informed any anomaly whatsoever to the local authorities. They even conducted various awareness campaigns across villages, schools and colleges.

“It is the youth that can help us in bringing about the change, so raising awareness in schools and colleges is an integral part of this multifaceted approach for preventing hunting practices. In order to build and strengthen trust with the communities, we have also been conducting medical camps and various other welfare initiatives,” says Meghna, while adding that owing to these efforts in East Medinipur and Howrah, they recorded a reduction in hunting practices by 95 percent in 2019.

A Long Road to Destination

While the impact in the southern part of Bengal has been exemplary, the other hunting festivals across the state continue to be a challenge. In a move to curb the practice of ritualistic hunting in districts of West Medinipur, Jhargram, Purulia, Bankura and Murshidabad, HEAL filed another PIL before the Calcutta High Court. The court order dated April 18, 2019, directed the Chief Wildlife Warden of the Forest Department to take all necessary measures to stop all hunting practices. In the last one year, efforts of awareness among local communities and monitoring of hunting spots have vigilantly been carried out by HEAL members along with the district officials.

“We haven’t been entirely successful to put an end to ritualistic hunting in these regions yet, but the COVID-19 lockdown surprisingly has played an important part in deterring this practice due to restrictions on transport, making the hunts smaller and more sporadic,” she adds. The focus she says is to inspire youth to not hunt but protect their backyard wildlife.

In addition to sensitization, awareness, training and monitoring programs, HEAL is also conducting a series of detailed hunting surveys across Jhargram, Bankura and West Medinipur in association with the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT) and Wildlife Trust of India (WTI). This survey is being done to create a detailed hunting calendar and map that could prove to be extremely helpful in nabbing the poachers and hunters across the region.

“Ours is a multi-pronged approach; this calendar will not only facilitate accurate monitoring of communities and hunting spots but also help us understand how to and where to better implement our awareness and sensitization programs. Communities, especially their youth, need to realize that their fit of fun comes at such a huge prize. They need to understand the large scale environmental impact of their actions, especially on the future generations,” she concludes.

(Edited by Sandhya Menon)